For lead Sandy Hook detective, it’s about ‘what’s best for the victims and the victims’ families’

H John Voorhees III/Hearst Connecticut Media

TREVOR BALLANTYNE

Dec. 7, 2022Updated: Dec. 7, 2022 1:54 p.m.

For retired Connecticut State Police Detective Daniel Jewiss, the driving force behind the police work performed in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook school shooting came with a simple message posted on bulletin board in the command center. “The first thing I wrote on it was: “What’s best for the victims and the victims’ families?” recalled Jewiss, the lead investigator into the Sandy Hook shooting for the state police. “Everything we did investigatively, after that, instead of going back to (what) our policy was or what we normally would do or what a boss would say, we would first ask that question and that drove what we still do today, which is 'what is best for the victims and their families?'”

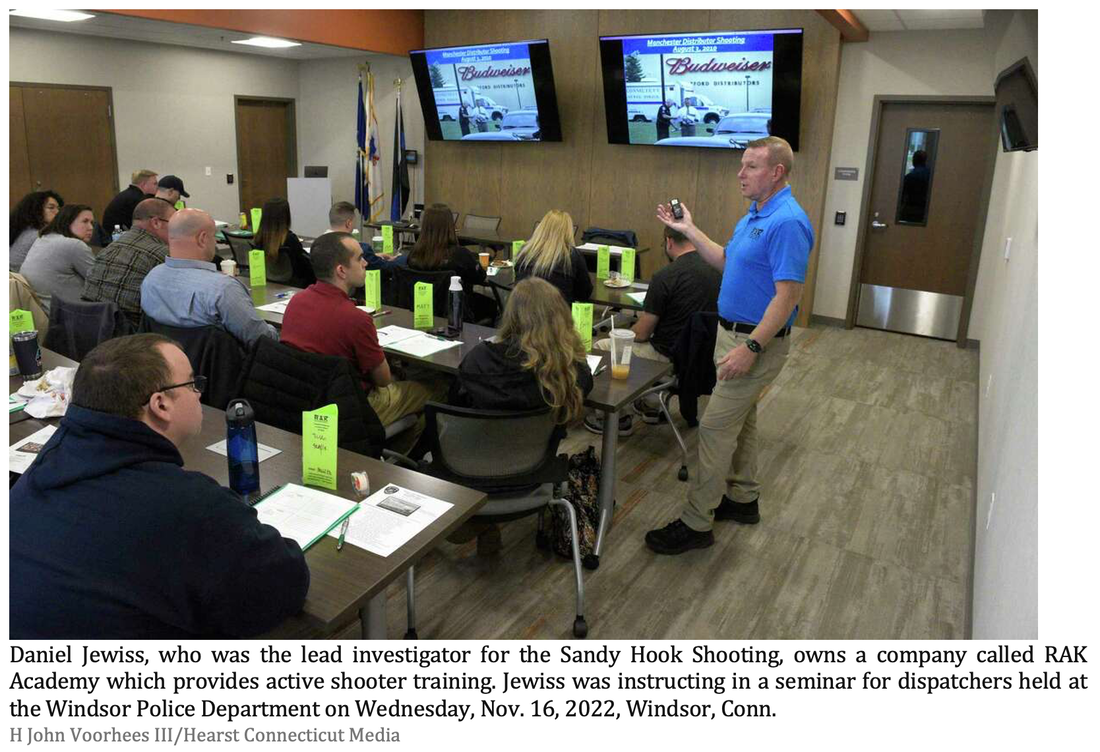

Jewiss, who joined the state police in 1998, retired a few years ago after a 23-year career. Rather than truly retire, however, Jewiss took some of his learnings from one of the most tragic shootings in American history and founded his own consulting firm, RAK Academy. His goal is to teach law enforcement officers and emergency dispatchers techniques for responding to “active killers” with the primary goal of "saving lives," according to the company's website.

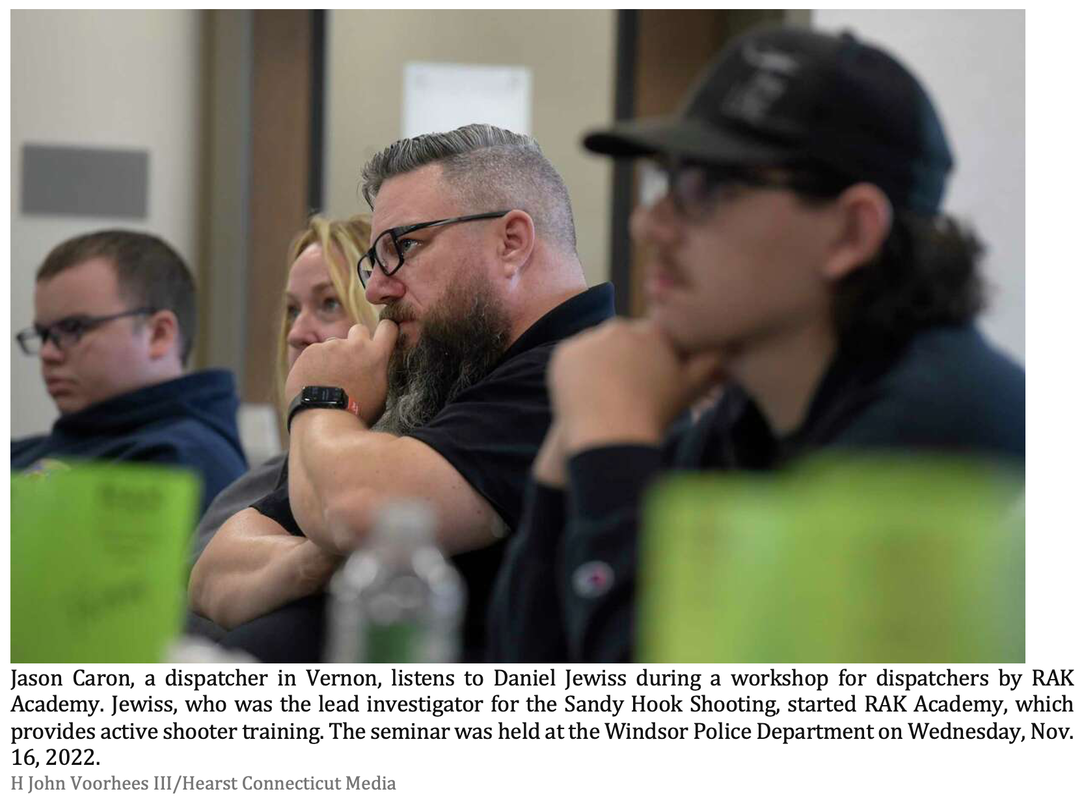

Jewiss said last month that there's been high demand, particularly with instruction he provides to police departments to help guide dispatcher techniques which become crucial in any mass casualty event.

The retired officer noted dispatchers with the Connecticut State Police are required to attend an eight-week training course, but most departments across the country treat the role as an administrative position and training regiments are often lacking. “It’s the biggest gap because there is just not enough good dispatch training out there,” said Jewiss.

“It’s so important and they are so undervalued, and they are under-trained,” he added. “There’s no mental health support, it’s really a shame of what they go through, when they deal with the worst kind of scenarios, (police officers) deal with, it’s just that they aren’t physically there but they are emotionally there and what they do is absolutely key to what we do.”

In addition to honing in on the dispatch strategy, Jewiss also works with school districts, businesses and churches to implement strategies for saving lives in mass casualty events. For police departments, the RAK Academy also helps investigators and members of the command staff around how to work in the weeks, months, and years following an active killer situation.

Initially, officers must stop a threat, he explained, then they transition to saving lives, “but then there is also other, longer-term ways to start saving lives by lessening trauma, so there needs to be some type of game plan that they can pull out and walk through when they are in the middle of it.”

That was the approach for Jewiss and his colleagues, who took more than a year to complete their investigation into Sandy Hook, even though there would be no prosecution in a criminal trial. The focus was still on finding the facts to help inform the families who might otherwise not have the truth — even if it was worse than they could imagine.

"It’s our job, not to make it easier, but to just find the facts and to share those facts in a respectful manner with them,” he said.

But it’s not just about tactics. By sharing the unforeseen challenges and decisions encountered by Jewiss and other investigators in the aftermath of the school shooting 10 years ago, “both good and bad,” the academy also provides a road map to prepare police investigators and command staff for the “enormity and uniqueness” of their role, particularly when it comes to the victims and their families.

In an interview in August, the former detective explained how in many cases that means throwing policies out the window, breaking procedures and, sometimes, even breaking the law.

In one of those decisions, Jewiss recalled how he and his team ignored the legal requirement to obtain a court order needed to release personal belongings to the victims’ families. “We never asked for permission. We just gave it back to them. It’s not like we told everybody but the command staff knew what we were doing and that we were OK with it,” he said. In another example, the former detective recalled how he and fellow detectives refused orders from their superiors who asked them to collect witness statements from the surviving students. “We were adamant that we were not going to knock on those doors, if they came to us it was going to be different, but we were not going to do that. It got heated” he said. “We stood down as detectives and said ‘we are not doing that’ and to their credit they had the humility to give in.” Beyond Sandy HookIt wasn’t just Sandy Hook where the importance of finding ways to serve and support victims became evident. When Jewiss joined the State Police, he said didn’t feel like he was overly zealous, but he certainly remembered being “hungry.”

“I just thought I am going to find people with drugs and I am going to arrest people and I am going to catch people,” he remembered. But in teaching cadets at the police academy later in his career he said the lessons he gave became more about “the way you go about that and just the way you focus was huge.”

Jewiss recalled one day a fellow patrol officer told him about a car crash he had responded to that took the life of a young woman, describing how he “held her in the driver seat and tried to keep her airway open but unfortunately too much damage had been done and she died.” In the months and years that followed the officer remained closed to the girls' family and started a fundraiser to support them.

“I felt like, what the hell am I doing? He was focused on just so much deeper things than I was," Jewiss said. He began giving holiday cards each year to a family he worked with. "I couldn’t do it just for myself but I had to make sure it was going to work for them," he said. "But it also meant that the whole year instead of just focusing on catching bad guys I was looking at how to serve victims."

When it comes to marking a decade since the Sandy Hook tragedy, Jewiss said the same type compassionate approach would guide his actions and presence around any of the ceremonies planned for that month. There would undoubtedly be connections made with former colleagues and others, but if he can support the families in any way, even if that meant keeping a distance, he would be ready.

“It’s just going back to doing what is right for their families,” he said. “That still going to be the first question.”

Written By Trevor Ballantyne

Trevor Ballantyne is an investigative journalist and covers the towns of Redding and Brookfield. He previously worked in Norwich, CT and in Massachusetts, where he won awards for his coverage of the pandemic's impact on Boston-area nursing homes. He holds a master's degree from Boston University and a bachelor's degree from Elon University.

H John Voorhees III/Hearst Connecticut Media

TREVOR BALLANTYNE

Dec. 7, 2022Updated: Dec. 7, 2022 1:54 p.m.

For retired Connecticut State Police Detective Daniel Jewiss, the driving force behind the police work performed in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook school shooting came with a simple message posted on bulletin board in the command center. “The first thing I wrote on it was: “What’s best for the victims and the victims’ families?” recalled Jewiss, the lead investigator into the Sandy Hook shooting for the state police. “Everything we did investigatively, after that, instead of going back to (what) our policy was or what we normally would do or what a boss would say, we would first ask that question and that drove what we still do today, which is 'what is best for the victims and their families?'”

Jewiss, who joined the state police in 1998, retired a few years ago after a 23-year career. Rather than truly retire, however, Jewiss took some of his learnings from one of the most tragic shootings in American history and founded his own consulting firm, RAK Academy. His goal is to teach law enforcement officers and emergency dispatchers techniques for responding to “active killers” with the primary goal of "saving lives," according to the company's website.

Jewiss said last month that there's been high demand, particularly with instruction he provides to police departments to help guide dispatcher techniques which become crucial in any mass casualty event.

The retired officer noted dispatchers with the Connecticut State Police are required to attend an eight-week training course, but most departments across the country treat the role as an administrative position and training regiments are often lacking. “It’s the biggest gap because there is just not enough good dispatch training out there,” said Jewiss.

“It’s so important and they are so undervalued, and they are under-trained,” he added. “There’s no mental health support, it’s really a shame of what they go through, when they deal with the worst kind of scenarios, (police officers) deal with, it’s just that they aren’t physically there but they are emotionally there and what they do is absolutely key to what we do.”

In addition to honing in on the dispatch strategy, Jewiss also works with school districts, businesses and churches to implement strategies for saving lives in mass casualty events. For police departments, the RAK Academy also helps investigators and members of the command staff around how to work in the weeks, months, and years following an active killer situation.

Initially, officers must stop a threat, he explained, then they transition to saving lives, “but then there is also other, longer-term ways to start saving lives by lessening trauma, so there needs to be some type of game plan that they can pull out and walk through when they are in the middle of it.”

That was the approach for Jewiss and his colleagues, who took more than a year to complete their investigation into Sandy Hook, even though there would be no prosecution in a criminal trial. The focus was still on finding the facts to help inform the families who might otherwise not have the truth — even if it was worse than they could imagine.

"It’s our job, not to make it easier, but to just find the facts and to share those facts in a respectful manner with them,” he said.

But it’s not just about tactics. By sharing the unforeseen challenges and decisions encountered by Jewiss and other investigators in the aftermath of the school shooting 10 years ago, “both good and bad,” the academy also provides a road map to prepare police investigators and command staff for the “enormity and uniqueness” of their role, particularly when it comes to the victims and their families.

In an interview in August, the former detective explained how in many cases that means throwing policies out the window, breaking procedures and, sometimes, even breaking the law.

In one of those decisions, Jewiss recalled how he and his team ignored the legal requirement to obtain a court order needed to release personal belongings to the victims’ families. “We never asked for permission. We just gave it back to them. It’s not like we told everybody but the command staff knew what we were doing and that we were OK with it,” he said. In another example, the former detective recalled how he and fellow detectives refused orders from their superiors who asked them to collect witness statements from the surviving students. “We were adamant that we were not going to knock on those doors, if they came to us it was going to be different, but we were not going to do that. It got heated” he said. “We stood down as detectives and said ‘we are not doing that’ and to their credit they had the humility to give in.” Beyond Sandy HookIt wasn’t just Sandy Hook where the importance of finding ways to serve and support victims became evident. When Jewiss joined the State Police, he said didn’t feel like he was overly zealous, but he certainly remembered being “hungry.”

“I just thought I am going to find people with drugs and I am going to arrest people and I am going to catch people,” he remembered. But in teaching cadets at the police academy later in his career he said the lessons he gave became more about “the way you go about that and just the way you focus was huge.”

Jewiss recalled one day a fellow patrol officer told him about a car crash he had responded to that took the life of a young woman, describing how he “held her in the driver seat and tried to keep her airway open but unfortunately too much damage had been done and she died.” In the months and years that followed the officer remained closed to the girls' family and started a fundraiser to support them.

“I felt like, what the hell am I doing? He was focused on just so much deeper things than I was," Jewiss said. He began giving holiday cards each year to a family he worked with. "I couldn’t do it just for myself but I had to make sure it was going to work for them," he said. "But it also meant that the whole year instead of just focusing on catching bad guys I was looking at how to serve victims."

When it comes to marking a decade since the Sandy Hook tragedy, Jewiss said the same type compassionate approach would guide his actions and presence around any of the ceremonies planned for that month. There would undoubtedly be connections made with former colleagues and others, but if he can support the families in any way, even if that meant keeping a distance, he would be ready.

“It’s just going back to doing what is right for their families,” he said. “That still going to be the first question.”

Written By Trevor Ballantyne

Trevor Ballantyne is an investigative journalist and covers the towns of Redding and Brookfield. He previously worked in Norwich, CT and in Massachusetts, where he won awards for his coverage of the pandemic's impact on Boston-area nursing homes. He holds a master's degree from Boston University and a bachelor's degree from Elon University.